The Lend-Lease Act, 1941

On 9 February 1941, just five months after the Royal Air Force had fought the Luftwaffe during the Battle of Britain in 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ended his wartime broadcast by pleading with President Franklin Roosevelt to:

Give us the tools, and we shall finish the job.

Churchill called upon the President of the United States to intensify American efforts to supply Britain with key materials needed for the war effort. Public opinion in the United States was polarised as to whether America should provide aid to Britain and its Allies, including the Soviet Union, during the early stages of the Second World War.

Roosevelt believed that the United States of America should serve as a great 'Arsenal of Democracy' on the world stage, and this view was shared by many in Congress (the branch of federal government responsible for legislature). There was, however, a large dissenting group within his own political party and in the opposition. There were many prominent non-interventionists, such as the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh who led a popular movement called 'America First', devoted to preventing American involvement in another world war.

The Neutrality Acts originated from American involvement in the First World War (1914-1918). There was a belief in America that involvement in the conflict had been driven by financiers with business interests in Europe. With the threat of war looming during the 1930s - America decided to guard itself against future involvement in a world war by enforcing three Neutrality Acts.

The final act of 1939 was particularly important as Roosevelt managed to lift an arms embargo enforced by previous legislation, which allowed America to trade with the belligerent nations. This meant Roosevelt could assist the Allies on a 'cash and carry' basis, but the Allies would have to supply their own ships and pay cash to collect the goods.

On 3 July 1940 Churchill requested aid from the United States and on 2 September 1940, Roosevelt responded by exchanging 50 American warships for a 99-year lease. This ignited a major policy debate in the United States between the non-interventionists and those wanting a formal aid agreement.

By February 1941, American support for Britain had increased in the aftermath of the Blitz (7 September 1940 - 10 May 1941) and the Battle of Britain (10 July 1940 - 31 October 1940). American CBS Europe reporter, Ed Murrow, encouraged public sympathy in the United States through his rooftop reports in London during Luftwaffe air raids in 1940.

Peabody Award winning broadcast journalist Bob Edwards wrote in 2004:

'he (Murrow) brought WWII into the living rooms of American homes' and 'Murrow's reports of a brave Britain standing alone was just what London wanted Americans to hear and might galvanise some support from Washington'1

There was also a need to show that a European country could survive a Nazi onslaught, and the resistance displayed by RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain successfully achieved this. A perception of Britain standing alone against tyranny was cultivated by the British and Pro-British American media, which helped to further solidify Anglo-American relations. This propaganda victory proved the final defeat for the non-interventionist voices.

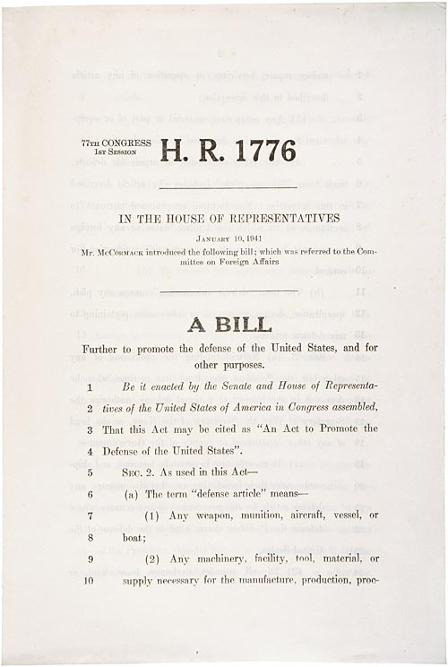

Following 2 months of fierce debate, Roosevelt and his political Allies were victorious. Congress passed the historic Lend-Lease Act, which came into law on the 11 March 1941. The Lend-Lease Act formally rendered the Neutrality Acts of the 1930s obsolete and provided Britain and its Allies with armaments, food and raw materials to continue fighting the war.

1. Edwards, Bob: 'Edward Murrow and the Birth of Broadcast Journalism' (Wiley Publishing, 2004)